Routine, in an intelligent man, is a sign of ambition. —W. H. Auden

Study the lives of great writers, thinkers, artists, and entrepreneurs, and you'll find that most of them were people of routine.

Whether it's Benjamin Franklin's rigorous schedule, Anthony Trollope's intense early morning writing sessions, or entrepreneur Sam Corcos meticulous two-year time-tracking experiment, routine is the rule—with few exceptions.

But why is routine so crucial, especially today? How can you craft one that propels you towards your goals and the life you envision? And most importantly, how do you stick to a routine and not give up? This guide answers those questions. You’ll discover:

The philosophy of routine: why it matters (more than you think it does)

Principles for routine design: avoiding complexity, top goal orientation, time-tested strategies vs. experimentation, and prioritization.

Routine & energy management: the goldilocks zone of challenge, rest & creativity, working with your natural cadence.

Principles for creating a powerful daily routine: Core systems, supporting rituals and rules, morning & evening structure, fluid vs rigid scheduling, and more.

Principles for creating a momentum-centric weekly routine: Weekly review process, themed days, physical training for cognitive output (and how to schedule it), thinking time, and more.

How to stick with it and not quit: creating an accountability system, deepening the groove, progress > perfection, avoiding self-sabotage, leveraging intrinsic & extrinsic motivation.

The Philosophy of Routine: Why It Matters

I used to be a romantic creative who looked down upon routine. I wanted freedom, not structure. And reading The Four Hour Work Week at a young age only reinforced this.

After leaving school, I lived at home for a year while building my online business (EDMProd). I had the luxury of being able to manage my own schedule and use time how I pleased.

And so I did exactly what most 18-year-olds would do. I worked when I wanted and how I wanted. That meant slamming back an energy drink at 9pm on a Wednesday night and working through to the early hours of the morning, then taking the next day off to play video games. It meant watching Breaking Bad at noon while eating lunch (which often ended up taking over my entire afternoon). I had no routine, no rhythm, and no consistency.

I still made it work. The business grew. I got things done. But at a much slower rate than I could have. It wasn’t until I adopted a consistent routine years later that I realized how damn unproductive I was during this time. Sure, it was fun. I look back with fond memories. But I wasn’t effective, nor disciplined.

What I didn’t understand was that without structure, you get pushed around by impulse. You get pulled into whatever is most interesting or appealing to you at any given moment. Or you spend an unnecessary amount of time trying to decide what to do and get stuck in overthinking loops.

This is why the first version of my book The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity, that I started during my first year building the business took well over a year to write. There was no plan or deadline. No, “I’m going to write for 3 hours every morning until this is done.” I simply wrote when I wanted to, which happened to be rarely.

(The second version of that same book—a complete rewrite—took me one month to draft and edit. Why? Because I diligently wrote every day for at least 3-4 hours. I gave myself no excuses.)

The operator & the strategist inside your head

In terms of pure productive and creative output, an imperfect analogy shows us how critical it is to design and follow a routine.

Imagine yourself a manager of a factory designing widgets. You have an operator who works on some of the machines. When he asks you what he should be working on and how he should be working, you say to him, “These things should probably get done at some point, but figure it out for yourself and just play it by ear.”

Now, he might get some work done, but you’ve given him hardly any direction, zero deadlines, no structure. Every day he comes into work, the question on his mind is, “What the hell do I do? Where do I start?” And he expends a lot of energy simply trying to figure out what to work on before even working.

Fortunately, you’re a smart manager. You’re a strategist. So you change course. You give your operator clear instructions and deadlines. You tell him, “For the next two weeks, this is the most important priority. It will probably require X many hours. Prioritize this before everything else, but also make sure that Y and Z are maintained.”

Now the operator has rules. He can come to work everyday with clarity. Is the work magically easy? No. It’s still work. But he doesn’t spend energy trying to figure out what the work is, he just does what he’s been assigned.

This factory exists inside your head, and is exactly why you must design and follow a routine. There’s a strategist/manager who knows what’s best for you given your goals.

You want to write a book? Well, you better write. Every day. For at least an hour. You better schedule that in. That’s the production function. If you don’t make it clear to yourself—the operator self—then it won’t happen. At least not consistently.

When you say to yourself, “I’m going to wake up at 5am every day and write for 2 hours before I do anything else.” Or, “I’m going to go to the gym before lunch 4 days per week.” You’re acting as the strategist who knows best. You recognize that that intention, that plan, is an improvement on whatever you’re currently doing—otherwise you wouldn’t have the thought in the first place.

The role of the operator self is to subjugate himself to the strategist. The strategist must be clear and direct, “This is what we’re going to do. Yes, I know there’s a part of us that doesn’t want to do the work, but we need to override that, and that’s why I’m putting this plan in place. If I don’t put this plan in place, I know that we’ll simply do what we want, when we want, and that leads to bad outcomes over the long term for both of us, right?”

Designing a routine is fundamentally the role of the strategist. Following that routine requires the operator to act as the operator, and not try to “outsmart” the strategist. In other words: the version of you who designed the routine for you to follow today is smarter than you are, and you better follow his instructions, even, and especially when you don’t want to follow them.

Routine is a reflection of seriousness and professionalism

Your best work is that which is fuelled by curiosity but completed through diligence and discipline. If you’re not interested or curious about building a business and try to discipline your way into entrepreneurship—good luck. If you’re interested in being a writer, and you love writing, but you aren’t prepared to write even when you don’t feel like it (exercising discipline), then good luck.

Deliberately designing and following a routine is an act of discipline, which is a reflection of your commitment to whatever it is you’re doing. Your craft. Your business. Your project.

The 18-year-old version of me who took over a year to write the first version of his ebook was fundamentally unserious and undisciplined. While I might have told people that I was “writing an ebook,” my actions showed otherwise. I certainly wasn’t writing every day, or week for that matter.

Routine is an act of defiance against a distracting world

The world doesn’t want you to be consistent, creative, disciplined or committed—at least not to your own personal projects.

It wants you to think that you can get away with just being an operator. Just “feeling it out” on any given day. But that isn’t a working strategy. It’s no match for the dopamine monsters around every corner. To avoid being a distracted zombie, you must at the very least have the intention to engage in more productive, useful activities. And then do the hard work of fulfilling that intention and making your desired routine second nature.

Following a routine is acknowledging that modern life is antithetical to focus and creativity. That without clearly defined boundaries, priorities, and blocks of time, we will be pulled away from the important work we should be doing. That’s if we even begin the work in the first place.

The fundamental purpose of routine

To sum up this philosophy of routine:

The purpose of routine is to create conditions that encourage right action.

You won’t always do the right action. You won’t always have the perfect workday. You won’t always enjoy it. But rest assured, if you design a routine and take it seriously, you will create the conditions that encourage focus, right actions, progress, and the completion of projects and important work.

Routine is about following clearly defined rules instead of vague ideals. It’s saying, “I’m going to write 2,000 words a day.” Instead of “it would be nice to write 2,000 words a day, let’s see how I feel.” The former is a condition that encourages right action. It’s precise. It’s black and white. It’s hard to ignore and rationalize your way around.

Fundamentally, routine is not planning your life down to the very minute. It’s the art and strategy of prioritization, gaining clarity, and exercising discipline. It’s defining what’s important, and then doing it. Day in and day out.

Principles of Routine Design

There’s plenty of “plug and play” routines from productivity gurus on the web, but how often to people stick to these routines? My guess is that adherence is rare. The more something is “templatized”, the less it’s thought through. And when it comes to creating a routine that helps you achieve what you want to achieve, it’s worth spending time thinking through what that routine should look like.

Let’s look at some principles that will help guide us here.

Unnecessarily complexity leads to failure. Useful routines & rituals are often simple.

We have a bias toward thinking that the complex is somehow better than the simple, something I talked about in The Complexity Trap. We somehow think that the morning routine with 10 habits is better than the one with 5. The more, the better. Even when we know of this bias, we still fall victim to it again and again. This is because, the desire for complexity is somehow linked to avoidance of the simple work that matters.

The more preconditions you put in place before you can take action, the longer you can delay the inevitable resistance that hits you when you sit down to do your important work. Complexity gives you places to hide.

There’s nothing wrong with having a morning routine, even one that has multiple rituals and habits. But if it’s inhibiting your ability to take action on the work that matters, how useful is it? You do not want to become the person who constantly “optimizes” their performance through a stack of habits only to never perform. You don’t want to become the person who does self-help for the sake of self-help—you want to put that energy towards something bigger than the self-help meta.

Fundamentally, you don’t want to add unnecessary complexity because it’s almost always a form of pseudo-productivity. It feels good at the start, but the lack of real progress eats away at you and you end up disappointed, unfulfilled, and lacking momentum.

Instead, make your routine as simple as it needs to be in order to effectively make progress towards your goals. If that means waking up, getting sunlight, drinking bone broth and coffee, grounding, reading for 20 mins because these things truly help you do the real work better, then all the more power to you. But don’t kid yourself. Most of the writers, creators, and entrepreneurs you admire have one thing in common: they treat the main thing as the main thing, and ensure the path to doing that main thing is simple and as frictionless as possible.

Which is why…

Your routine should be centered around the main thing.

“In your effort to attend all things, everything gets shortchanged and nothing gets its due.” —Gary Keller, The One Thing

There’s far more to be gained by intensity and focus than by trying to solve multiple problems or push forward on multiple goals at once, and any routine that doesn’t encourage the former is suboptimal.

That’s not to say that you should neglect aspects of your life that aren’t the main thing. My main thing is to create 100 videos, but that doesn’t mean I don’t spend time on my other business projects, or exercise, or spend time with friends or family. But I only have one main thing, and everything else in my routine (at least right now) is built around that main thing.

The question to ask is: “How can I design a routine that enables me to make rapid progress on my main goal without unnecessarily sacrificing other important aspects of my life?”

For example, I might be able to hit my 100 video goal faster if I dedicated 12 hours a day to it. But that would affect my training schedule, my other responsibilities, and might even reduce the quality of my output. I would unnecessarily sacrifice other important aspects of my life.

My current routine is more like ~4 hours of focused work on this goal each day. I have to sacrifice some aspects of my life to achieve this. I don’t go to 6am BJJ classes even though I love starting the day that way (it interferes too much with my prime focus hours, so I go at noon instead). I read in the evenings to help generate ideas for videos instead of relaxing and watching TV. But I’m happy with these tradeoffs.

As much as I can, I want everything in my routine to support the main thing. My simple morning routine, which involves waking up, moving around for a bit, reading for 20 mins in front of my red light device with a cup of coffee supports my ability to do the deep, focused work that matters. I don’t need to read, I don’t need the red light, but these habits support and don’t interfere, whereas a hard AM workout does interfere (at least for me).

If there’s one thing you take away from this article, make it this: focused work for a couple hours every day on your top goal is everything. So few people do it. It’s actually insane. Most people don’t get anywhere near 2 hours of deep work per day on their most important projects. If you need to make it as simple as possible: do the deep work, do it well, do it every day, and forget everything else.

90% Time-Tested Strategies, 10% Experimentation

Designing an effective routine is not a process of pure experimentation. You do not need to reinvent the wheel. There are first principles—truths—that have been figured out by others, such as:

You need long hours of uninterrupted focus to do good work.

Most people work best in the morning.

Poor sleep, lack of exercise, neglect of rest will harm you in the long term and affect your ability to do work.

This list could go on. The point is that you should be wary of thinking you’re unique and different when you’re not. Yes, of course there are exceptions. Bukowski was a raging alcoholic and had a terrible sleep schedule and would have scoffed at an article like this. I also have no desire to live the life he lived. I don’t even like his writing. You are not Bukowski.

Your routine should be founded upon these time-tested principles. It should look similar to the routine of others who have achieved (or are working towards achieving) the same goals you are. That’s why writer’s schedules are so similar: they wake up, and they write, with intense focus, for hours. There’s no escaping this.

You can experiment and optimize on the margin. Do you work better first thing in the morning like Anthony Trollope? Or are you more effective after a slow, relaxing morning with some reading and coffee? Do you operate best in 90 minute focused work sessions, or 60 min focused work sessions?

What you want to avoid is premature experimentation, especially if you’re someone who’s been inconsistent and lacking momentum for a while. Following a routine is hard at the beginning. And when you’re faced with that challenge, it’s easy to change something for the sake of change.

For example, you decide that your new routine is to wake up at 5am and do focused deep work for 2 hours on your most important task. The strategist in your mind considers this the best routine you can follow. But it won’t be easy. And within the first few days, you’ll likely find endless excuses for why the routine “doesn’t make sense” and why you should change it. But you’re a few days in. Of course it’s going to be uncomfortable. You’re breaking out of stasis. Discomfort doesn’t always mean you should change course. Often, the best strategy is to simply double down and continue on the path.

Good routine is the art of prioritization

Some people like to follow the calendar method: scheduling every activity (and non-activity) in their calendar, down to the minute. If that’s you, great.

It’s not me. My calendar is almost always bare and empty aside from calls/meetings. I don’t schedule focus sessions in. I don’t schedule gym sessions in. Only events that involve other people.

My workday is not bare and empty. I have a set of cascading priorities, that on a day-to-day basis differ in length, but always get done. And that’s what makes up my routine. It’s a dynamic routine that can be executed regardless of what time I wake up and start work, and it’s flexible enough to ensure that I make consistent progress even on my worst days.

It looks something like this:

Deep work - writing. This is priority #1 and no other work should happen prior at least 60 mins of this.

Other demanding work/deep work (non-writing).

Exercise

Less demanding work (admin, email, etc).

Reading

Leisure

And generally, my day follows that set of priorities from the top down. I work in the morning, exercise when my brain needs a rest, come back and do some more work, then read and wrap up for the day. I’m also flexible enough to follow flow where it leads me (last night, for example, I did another deep work session after coming back from the gym because I was curious about a business idea that I wanted to think through and explore). So this isn’t a concrete routine.

If you’re not the meticulous calendar type, then viewing routine as prioritization may be helpful to you.

Routine should not be a crutch

You should be able to work wherever, whenever. Routine is just something to make you more effective and consistent. But you want to be the person who can operate and focus in even the worst conditions, and this is largely a mentality thing.

Routine, energy and recovery

“Energy, not time, is the fundamental currency of high performance.” — Jim Loehr & Tony Schwartz

An athlete follows a training schedule that challenges and grows them, but also provides room for rest and recovery. They can’t train all the time otherwise they’ll break down.

The mental athlete—the knowledge worker—must do similar. When designing a routine, you are not programming a robot that can operate 24/7. You’re programming you, a human, with unique biochemical processes and physiological needs. You must create a routine that maximizes energy by balancing challenge, stress and rest.

Principle 1: Insufficient challenge lowers energy

We constantly hear about the necessity of rest, leisure time, non-work. But the inverse is also a problem: underworking, spending too much time in leisure, lacking sufficient demand on your cognition and resources. This destroys energy and spirit.

You adapt to the environment you’re in. And if your environment is one of ease, with little challenge or stress, then why would you expect to feel energized?

The challenge and demand needs to be meaningful, sure. Otherwise it’s just a grind. But fundamentally, if your routine—or lack of it—is not demanding enough, then you’ll quickly fall into a malaise. Somewhere, somehow, your body and mind recognize that you don’t need energy, and it will take the path of least resistance.

Of course, there is a golden ratio of challenge/ease. Make your routine too challenging and you’ll simply fail before you begin, or it will lead to unnecessary stress with marginal gains in the quantity and quality of your work. This requires some experimentation.

Principle 2: Insufficient rest lowers energy, creativity and quality of work

If you’re doing any type of knowledge work that requires you to produce good ideas and make wise decisions, then a lack of rest, recovery and leisure will not only destroy your physical and mental energy, but also the quality of your work.

In fact, if you’re someone who struggles with the concept of rest, then you need to reframe it. Often, the best ideas come to you when you’re not working. And if you don’t create non-work time in your routine, then you’re missing out on leverage.

Rest and leisure are conducive to your work and professional goals. There’s a reason why writers and thinkers of past (and present) spent so much time not working.

Principle 3: Work with, not against your natural cadence

We all have slightly different ebbs and flows of energy throughout the day, and respond differently to activities like exercise. This is where routine experimentation comes in.

If I have a productive morning of writing where I hit 3-4 hours of deep work, the last thing I want to do at that point is sit down at the computer for another hour. So that’s when I exercise. I’ll hit the gym or go to BJJ.

Now, if I followed a preset routine from some entrepreneur guru on YouTube who told me to only go to the gym at the end of my workday, then I’d simply be a lot less effective. I’d be working against my natural cadence, an element of which is that I crave exercise around midday.

You have to trust your intuition without engaging in self-deception, which is the eternal battle. Sometimes, what you think is your natural cadence is simply resistance, the desire to procrastinate. Other times, it’s a legitimate signal that you should step away from work and go do something else.

This is why I think lower bound routine elements are useful. I force myself to do at least an hour of writing each day, even if I don’t feel like it at all. With that iron commitment, even if I deceive myself later in the day and rationalize not doing deep work, I’ve already done something.

Principle 4: Sprint, then rest

To repeat, you are not a robot. You cannot work as a machine does with the same focus and intensity for the entire day.

It’s much better to sprint, then rest. Focus with intensity, then pull back entirely. This is the antidote to the world of productive mediocrity and low-level busywork.

Principles for Designing a Daily Routine

Your daily routine is the engine of productive output and accomplishment. It should be carefully designed and taken seriously.

Most importantly, it should align with the goal(s) you want to achieve. It should incorporate the system(s) that helps you accomplish your goal(s). So we need to begin with the end in mind, designing our routine around and for the outcome we desire.

The core activity

As I mentioned earlier, our routine should be built around the top goal. The main thing.

“If there’s one thing you take away from this article, make it this: focused work for a couple hours every day on your top goal is everything.”

The piercing question from Gary Keller’s The One Thing is helpful here:

"What's the one thing I can do such that by doing it everything else will be easier or unnecessary?"

If your top goal is to write a book, then you better write. That’s the one thing.

If your top goal is to grow your business, then identify what the needle mover is. Maybe it’s building a new product, maybe it’s a marketing campaign, maybe it’s hiring a new staff member. Identify the one thing. Find the core activity.

I would strongly consider scheduling this core activity in your calendar, especially if you’re doing it on the side (either before or after work). Make it a real commitment. Make it sacred time.

I personally don’t schedule my core activity in my calendar, but it is the first big thing I do each day no matter what.

Other needle movers

You might struggle to find this core activity because you have multiple areas of responsibility, or you’re running a business that requires you do more than “one thing.”

Even in this case, you should still define a core activity. There is still something that is more important than everything else (it doesn’t mean everything else is unnecessary—this is simply an exercise in prioritization). This requires thinking. It’s hard.

Once you’ve done that, it’s worth defining the key needle movers that should be done on a daily basis.

For me, writing is my core activity. It is the work from which everything else flows. If it doesn’t get done, or I’m not consistent with it, everything else starts to suffer. Second to that, there are other needle movers: content ideation and production (filming, editing), building product, exercising and movement.

And so I want to design my routine around my core activity and my needle movers.

Rituals and rules

Working on the core activity and the needle movers is challenging, and you want to create and adhere to specific rituals and rules that help you do this work.

These are the small hacks and habits that have outsized impact over time. For example, I use SelfControl on mac to block social media websites until noon each day. This radically reduces my propensity for distraction. It’s impossible to overestimate how powerful this system is. It’s so simple and obvious, but extremely impactful.

Think through the rituals, rules and optimizations that would benefit you. Here are some of mine:

No caffeine past 12pm. Otherwise my sleep, and then my work suffer.

10k steps a day. Movement makes me feel good and creative. Walking gives me ideas too.

Active breaks away from the computer. Get outside. Move around.

SelfControl app blocking websites.

No calls until the afternoon (unless absolutely necessary)

To me, these rituals, rules and other practices are what create the ideal day. If I get solid deep work done, avoid social media, exercise, and spend time with others, then it’s a great day.

Morning routines

“Take excellent care of the front end of your day, and the rest of your day will pretty much take care of itself. Own your morning. Elevate your life.”

There’s ongoing debate around whether you should even have a morning routine, or just get straight to work like Alex Hormozi says.

I lean towards the “getting straight to work.” Even though I think it’s nuanced. I’ve tried it all, and I’ve found that my days are significantly more enjoyable and productive when I do a deep work session first thing in the morning (as I’m doing now while I write this script at 6am).

I think this is even more important if you’re trying to build something on the side before you go to your 9-5. It’s pretty hard to get solid work in if you wake up at 7am and then have a 90 min morning routine before you even get the chance to sit down and work on your side business.

But this is my personal take based on my personal experimentation, and I know plenty of people who do differently and are even more effective than I am. So, there’s no blueprint, but there are three principles I recommend following:

Waking up early is ridiculously overdone advice, but it still works. As Franklin said, “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.” There’s something about getting up early that gives you a psychological boost and builds momentum through the rest of the day. Obviously this requires you to get a great sleep, which is another topic by itself.

Do what gives you energy. For me, this is doing a deep work writing block ASAP. For others, this means going for a run or hitting the gym first thing. Or it might mean reading for 30 mins and filling your mind. You probably know what gives you energy, so just make it a consistent part of your morning.

Don’t delay your core activity work longer than necessary. Filling your morning routine with a bunch of optimizations might feel productive, but if you’re never doing the work that needs to be done, then what’s the point?

There’s probably value in having an evening routine too. I don’t really have one. I don’t schedule that stuff in. There are a few things I do personally which may work for you, and most of them revolve around ensuring I sleep well:

Blue-light blocking glasses and dim lights past 7:30pm. No screens ideally. This has been a game-changer for me.

Read fiction, history or biography before bed. No business, self-help, etc. Helps shut down my mind.

Chamomile tea + collagen + L-theanine + magnesium. Try it.

Weekly Routine Pillars

A good weekly routine is built by a good daily routine. But there is value in zooming out and looking at your entire week—especially if you have multiple areas of responsibility that can’t be integrated into a single day.

There are a few key principles and pillars that I recommend.

Batch/theme & structure your week

I have multiple projects and areas of responsibility. It’s too much to fit in one simple daily routine, and so I space this work out over the week.

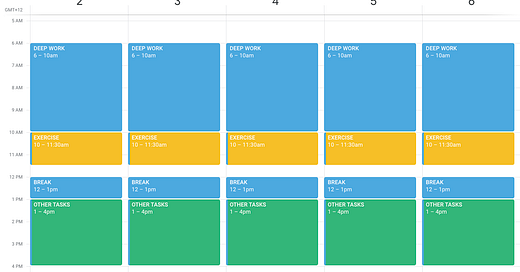

For example, Mon-Wed is heavy focus on YouTube content and writing (I do my core writing activity every day, but the start of the week I’ll do longer sessions). Thursday is usually a catch-up day. Friday is focused on my other business. Saturday is curiosity day or another catch-up day.

[EXAMPLE]

You can take this idea pretty far, especially if you’re in a position where you have some autonomy over your time:

Schedule meetings on a particular day every week (e.g., Fridays) so you have vast amounts of free calendar time to do the deep work.

Dedicate an entire day each week to one project or side project.

Have a “buffer day” where you execute on all the small tasks hanging over you.

Weekly review

I used to do a 1-hour weekly review on a Sunday and felt it made little difference to my life, so now I just answer a few simple questions either on Sunday afternoon or Monday morning before I start the week.

Those review questions are:

What went well?

What didn’t go well?

What did I learn?

What’s the 20% driving the 80% of results?

And then I answer some simple planning questions:

What’s the most important thing I can do this week?

What are the other 2-6 most important tasks I need to do?

How will I ensure maximum focus this week?

What might interrupt this?

All up, it takes me 15 mins and gives me clarity for the week ahead.

I think you should do something like this, even if it’s a quick review like mine. Otherwise it’s too easy to go week by week without any introspection or intention. You fall into doing a lot of busywork or heading in the wrong direction.

Thinking time

At least 30 mins a week, spend some time alone with pen and paper and just think through something.

It could be a problem in your business. It could be a relationship problem. It could be an idea you’re curious about and want to explore.

This is one of the highest leverage things you can possibly add to your routine. It’s incredible how few people will do this.

Just the other day I was talking to an entrepreneur friend who’s extremely busy and feels like he’s on a hamster wheel. He told me he needed a better structure and routine, otherwise nothing was going to improve. I told him that until you can step back and set aside 30-60 mins to think from a birds-eye perspective, nothing is going to improve. So that’s what he did, and then he realized there were some easy improvements he could make, and he made them, and things improved.

It’s so radically simple, but it works. You should schedule this in your calendar if you know it’s not going to happen otherwise. Make it something you do at least once per week.

How to stick with it and not quit

You’ve got the knowledge and principles, and some idea of how you should craft your routine. But how do you actually stick with it? Intention is one thing, commitment and stickability another.

Create a system for tracking and holding yourself accountable

You want data to show that you’re actually progressing and doing the work. Not only does this help you avoid kidding yourself (most people don’t work as much as they think they do), it’s also highly motivating to see definitive progress.

I like to track my work/focus sessions in a simple daily note. I don’t track every minute of my day. Only work time.

After each work session, I fill out a simple Google Form that autopopulates into a shared spreadsheet with my brother, who also follows the same process. It’s great for accountability (something I do with my coaching clients too)

You can use this system, you can use an app like Rize, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that you have some sort of intentional tracking system. The simpler the better.

Don’t aim for perfection, aim for change.

People fall off routines because they mess up one day, and let that day become two days, and then a week, and so on. They’re back to where they started, usually with some rationalization around why the routine was the problem, not them.

If your standard is perfection, then you will always fail. The better mental frame to operate out of is one of progress. You want to stack the good days, and make them more common than the bad days. Failing to stick to your routine for a day, or even a week, is not a sign that it’s a bad routine or you should change it. You need to take the wider view and look at your progress/change over time.

If you’ve had a bad few days, but you’re 2x as productive as you were a month ago, then you’re winning.

Lower-bound commitments

Because bad days are inevitable, you want an intuition for what you can do on those days to continue moving forward and sustain momentum.

For example, I like to follow a fairly demanding routine. My ideal daily routine is hours of deep work, a hard workout, 10k steps, reading, and other habits. But I know that there will be days where I wake up exhausted, or I’m getting sick, and there’s no way I’m going to hit my standard routine.

Sometimes, the best thing to do on these days is rest and take the day off. But most often, I fall back on my “lower bound” routine and do the 1-2 things that will leave me feeling accomplished and sustain momentum. It might be a 60-min writing session and some light reading.

Don’t underestimate dogged consistency, even if that dogged consistency seems small and insignificant on a given day.

Remind yourself of your why: both extrinsic and intrinsic

You should have multiple reasons for sticking to your routine, and be able to remind yourself of them when you feel like giving up. It helps to have extrinsic and intrinsic motivations that you can “stack” to convince yourself into productive states.

Why do I follow my deep work routine? Intrinsically, because it makes me feel good. I love flow states. They make me happier, more fulfilled. This is often motivation enough to do the work—because it will improve my general emotional state.

Second, following my routine mirrors back to me the person I want to become. I want to be someone who’s focused, on the path of personal growth. This is a challenge I’m rising up to and it feels good, intrinsically (extrinsically, it also feels good to be “seen” as someone of this character—another motivating factor).

And extrinsically, I know that if I follow my routine, then I’ll improve my chances of success. I’ll make more money. I’ll do better work and gain respect. My brand will grow. My status will increase. And so on.

You likely have a stack of reasons why you want to follow a routine. Write them down. Remind yourself of them.

Take action

With these principles in mind, it’s time to build your new routine (or improve your current one).

Set aside some time to really think through this. It’s the engine of your productive output, and should be taken seriously.

Three fundamental principles to keep in mind:

Keep it as simple as it needs to be, but no simpler. Unnecessary complexity leads to failure.

Your routine should be centered around your most important activity/top goal.

90% time-tested strategies, 10% experimentation.

Finally, remember that routine design is an iterative process. You won’t nail it from day one. It’s better to get something on paper and then start executing and figuring out where improvements can be made. You don’t want to be the person who endlessly plans and designs things but never takes real action.